By: Mickey Rubin, PhD, Executive Director of American Egg Board’s Egg Nutrition Center

July 15, 2020

Today is an important day for the American diet and for eggs. In an historic first, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee today issued recommendations for birth to 24 months old and specifically recommended eggs as an important first food for infants and toddlers, as well as for pregnant and lactating women.

Today’s Scientific Report also highlighted the importance of a nutrient plentiful in eggs – choline – while recommending eggs as a first food for babies to reduce risk for an egg allergy. The Advisory Committee additionally encouraged eggs for pre-teens and adolescents.

Eggs are one of the best sources of choline, an essential nutrient critical for fetal brain development. The Advisory Committee classified choline as an important nutrient that is under-consumed by all Americans. Importantly, 92% of pregnant women fail to meet the daily Adequate Intake (AI) recommendations for choline.

The Advisory Committee also specifically recommended eggs as an important first food. The latest research on food allergy prevention recommends introducing eggs when your baby is 4-6 months old and developmentally ready to help reduce the chances of developing an egg allergy. Eggs are an important first food as they provide eight essential nutrients that help build a healthy foundation for life.

Eggs are a nutritional powerhouse that contribute to health and wellbeing at every age and life stage, providing critical nutrients including protein, choline, riboflavin (vitamin B2), vitamin B12, biotin (B7), pantothenic acid (B5), iodine and selenium, which are valuable for supporting muscle and bone health, brain development and more. The Advisory Committee also noted eggs are a source of vitamin D, a nutrient of public health concern because it is under-consumed by all Americans.

Additionally, the Advisory Committee reinforced the strong body of evidence that dietary cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern. The science on eggs and cholesterol has been steadfast. The vast majority of scientific evidence shows egg consumption is not associated with cardiovascular disease. In fact, a recent Harvard University study that evaluated more than 30 years of data reaffirmed that eating eggs is not associated with cardiovascular disease. Leading health organizations such as the American Heart Association also state that eggs can be part of heart-healthy diet patterns.

As Americans are building healthier diets, you can count on eggs. For more information on building a healthy diet with eggs, please visit EggNutritionCenter.org.

Early introduction of eggs may reduce the risk of developing an egg allergy

By: Jen Houchins, PhD

Previous recommendations for infant feeding included guidance to avoid early introduction of eggs and allergenic foods in the diet for both the infant1 and mother.2 However, science has advanced, and early life feeding recommendations are rapidly changing. The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) evaluated evidence for complementary feeding, and allergy experts chimed in with the latest scientific evidence.3 The Advisory Committee affirmed that current research indicates that introducing peanut and egg, in an age-appropriate form, in the first year of life (>4 months) may reduce the risk of allergy to peanut and eggs. For other type of potentially allergenic foods, the DGAC reported there is no evidence that avoiding such foods in the first year of life is beneficial.

LATEST RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EARLY INTRODUCTION

The Advisory Committee recommends that caregivers provide a variety of animal-source foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy), fruits, and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and whole grain products, beginning at ages 6 to 12 months in order to provide essential nutrients, develop acceptance of nutrient-rich foods, and help build lifelong dietary habits. Additionally, early introduction of peanuts and eggs has the potential to favorably influence risk of allergy to these foods.

According to a recent systematic review conducted for the USDA and the Department of Health and Human Services Pregnancy and Birth to 24 months project, “…there is evidence to suggest that introducing allergenic foods in the first year of life (>4 months) does not increase risk of food allergy or atopic dermatitis but may prevent peanut and egg allergy…Moderate evidence suggests that introducing egg in the first year of life (>4 months) may reduce the risk of food allergy to egg.”4 This conclusion aligns with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Clinical Report on early nutritional interventions, which states, “There is no evidence that delaying the introduction of allergenic foods, including peanuts, eggs, and fish, beyond 4 to 6 months prevents atopic disease.”5 A recent analysis of the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) randomized controlled trial found “early introduction was effective in preventing the development of food allergy in specific groups of infants at high risk of developing food allergy…Of equal importance was that early introduction of allergenic foods into the diets of the non-high-risk infants was not associated with any increased risk of food allergy.”6 High risk infants in this study were identified as those with visible eczema at enrollment and infants with food sensitization (IgE antibodies present to one or more of the six allergenic foods). In this secondary analysis, early introduction of egg reduced the risk of allergy for both infants sensitized to egg and for those who had moderate to severe eczema at enrollment. Food Allegy Research and Education (FARE) has also commented on this new study, and suggests, “Guidance on early egg introduction is likely to evolve as more evidence becomes available.”

BAKED EGGS ARE TOLERATED BY MANY CHILDREN WITH EGG ALLERGY

In the U.S., approximately 1% of all children, and about 12% of children with food allergies are allergic to eggs.7 Egg allergies are considered to have a high rate of resolution in childhood, with approximately 50% of children with egg allergy reaching tolerance between the ages of 2-9 years.8,9

Of significant interest, it has been observed that approximately 70% of children with egg allergy can tolerate extensively baked egg in foods like muffins or cakes (as opposed to lightly cooked eggs like scrambled or French toast).9-11 Several studies have suggested that introduction of baked egg in the diet of children who can tolerate these foods may help hasten resolution of allergy,9-11 with some data showing frequent ingestion increases the likelihood of tolerance compared to infrequent ingestion.12

Although these are promising observations, many of these recent studies lack adequate control groups, limiting conclusions of the impact of extensively baked egg on allergy progression or development of tolerance.11 So, while more research is needed to better understand the role of baked eggs to potentially alter the course of egg allergy, “…inclusion of egg and milk in its baked form may also have other benefits. It is reasonable to expect that liberation of the diet may boost nutrition, improve the child and family’s quality of life and reduce family anxiety, however, no studies have specifically investigated this.”11 Importantly, caregivers of children with egg allergy should consult the child’s physician before introducing extensively baked egg into the child’s diet.

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS OF EARLY INTRODUCTION

Early introduction of eggs into an infant’s diet has the added benefit that eggs provide various amounts of all nutrients listed by the American Academy of Pediatrics as essential for brain growth.13 Eggs additionally provide 252 mcg of lutein + zeaxanthin, carotenoids with emerging evidence linking to brain development and health.14,15 As a nutrient-rich food that is a good or excellent source of eight essential nutrients, including choline – a nutrient essential for brain development and health, incorporation of eggs into the diet early may not only reduce the risk of food allergy to egg, but also serve as an important food to support brain development.

Interested in more information?

- Handout: Eggs as a First Food Infographic

- Handout: Pregnancy and Birth to 24 Months toolkit

- Watch: LEAPing Past Food Allergies webinar

- Read: An Allergist Moms Guide to Preventing Egg Allergy

- Watch:Jessica Ivey on WBRC Fox 6 News

- Read: Eggs – An Essential Complementary Food

Check out these recipes for infants and toddlers:

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Sweet Potato Soufflé

- Recipe: Eggy Peanut Butter Muffins

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Oatmeal with Egg

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Egg Scramble

- Recipe: Savory Egg Veggie Pancake

- Recipe: Baby’s First Pancakes

- Recipe: Egg Veggie Casserole

References:

- Zeiger, R.S., Food allergen avoidance in the prevention of food allergy in infants and children. Pediatrics, 2003. 111(6 Pt 3): p. 1662-71.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics, 2000. 106(2 Pt 1): p. 346-9.

- Spergel, J.M., et al. Public comments to the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2020 1-July-2020]; Available from: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FNS-2019-0001-17765.

- Obbagy, J.E., et al., Complementary feeding and food allergy, atopic dermatitis/eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr, 2019. 109(Supplement_7): p. 890s-934s.

- Greer, F.R., S.H. Sicherer, and A.W. Burks, The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics, 2019. 143(4).

- Perkin, M.R., et al., Efficacy of the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study among infants at high risk of developing food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2019. 144(6): p. 1606-1614.e2.

- Gupta, R.S., et al., The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics, 2018.

- Sicherer, S.H. and H.A. Sampson, Food allergy: A review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018. 141(1): p. 41-58.

- Savage, J., S. Sicherer, and R. Wood, The Natural History of Food Allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2016. 4(2): p. 196-203; quiz 204.

- Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. and A. Fiocchi, Rare, medium, or well done? The effect of heating and food matrix on food protein allergenicity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2009. 9(3): p. 234-7.

- Dang, T.D., R.L. Peters, and K.J. Allen, Debates in allergy medicine: baked egg and milk do not accelerate tolerance to egg and milk. World Allergy Organ J, 2016. 9: p. 2.

- Peters, R.L., et al., The natural history and clinical predictors of egg allergy in the first 2 years of life: a prospective, population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2014. 133(2): p. 485-91.

- Schwarzenberg, S.J. and M.K. Georgieff, Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health. Pediatrics, 2018. 141(2).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central. 2019; Available from: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html.

- Johnson, E.J., Role of lutein and zeaxanthin in visual and cognitive function throughout the lifespan. Nutr Rev, 2014. 72(9): p. 605-12.

Eggs: An Essential Complementary Food

By Jessica Ivey, RDN, LDN

The Egg Nutrition Center partnered with Jessica Ivey, RDN, LDN to write this blog post.

Some parents are excited to introduce their baby to solid foods, while others find the process nerve-racking. No matter where they fall on the spectrum, this is an important milestone for baby and can be a fun family experience.

Most babies are ready for complementary foods around 6 months of age. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, there is not enough information to suggest which foods should be introduced first and in what order, but rather, it’s best to introduce a wide variety of single ingredient foods in any order.1 Different foods contain different nutrients, so a more varied diet will be more nutritionally complete. Also, food and flavor preferences are established early, so exposing infants to many different textures and flavors from an early age can help establish lifelong healthy eating patterns.

Previously parents were told to wait to introduce allergenic foods to their infants, especially if there was a family history of food allergies. But groundbreaking research2,3 has found that early introduction of potential allergens, including eggs, to an infant around 6 months of age helps to reduce the likelihood of developing an allergy to that food.

When considering first foods, parents should choose nutrient-rich foods with essential nutrients for growth and development. Eggs are a good or excellent source of eight essential nutrients, including choline and lutein, nutrients that are important for brain development, learning, and memory. Plus, eggs have all of the nutrients that the American Academy of Pediatrics lists as key nutrients that support neurodevelopment – which are protein, zinc, iron, choline, folate, iodine, vitamins A, D, B6 and B12, and long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids.4

There are several ways to incorporate eggs into an infant’s diet. Here are some ideas to consider:

- Hard-cooked egg yolk mashed on a spoon or once baby is ready, mashed egg yolk spread on a piece of toast cut into sticks that the baby can pick up.

- Mixed meals like Peanut Butter Sweet Potato Souffle, Peanut Butter Oatmeal with Egg and Peanut Butter Egg Scramble are perfect for continual exposure to peanuts and eggs.

- Omelets are a great way to enjoy eggs while trying a variety of mix-ins, like cheese or sautéed vegetables. The omelet should be cut into strips that can be easily picked up.

- These Savory Egg and Veggie Pancakes and Baby’s First Pancakes are both perfect for self-feeding, as are these Eggy Peanut Butter Muffins.

- Once a child develops a better use of utensils, Basic Scrambled Eggs become easier to eat.

- Older toddlers can advance to an Egg and Cheese Waffle Sandwich or Veggie & Cheddar Crustless Quiche.

If parents are having trouble getting their child to try new foods, remember that many babies and toddlers need to be exposed to the same foods multiple times before accepting them. Encourage parents to keep offering nutrient-dense foods, like eggs, and eat nutritious foods themselves! Babies and toddlers are more likely to try foods that they see their peers, siblings, and parents eating.

Resources:

- DiMaggio D, et al. Updates in Infant Nutrition. Pediatr Rev, 2017. 38(10): p. 456.

- NIAID Guildeines https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/guidelines-clinicians-and-patients-food-allergy

- AAP Guidelines https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2019/03/15/peds.2019-0281.full.pdf

- Schwarzenberg S, et al. Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health. Pediatrics, 2018. 141(2)

Free Webinar: LEAPing Past Food Allergies

By: Mickey Rubin, PhD

LEAPing Past Food Allergies: How and When to Introduce Potential Allergens

Reported food allergies have been on the rise for the last decade. Groundbreaking findings from research led to new guidelines recommending early introduction of peanut foods in infancy to reduce the risk of peanut allergies. But what about other allergens such as egg, milk, and fish? Join internationally recognized researcher and pediatric allergist, Dr. Gideon Lack, and food allergy expert, Sherry Coleman Collins, MS, RDN, to review the latest science and feeding recommendations for reducing the risk of food allergies.

After attending this webinar, the attendee will be able to:

• Describe the latest science and feeding recommendations for reducing the risk of food allergies.

• Utilize the latest research to guide patients and clients on when and how to introduce common allergens, including peanuts, eggs, and others.

• Incorporate the latest National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines on infant feeding practice into their patient and client education and counseling.

This webinar has been approved for:

1.0 CEU

1.0 AAPA Category 1 CME*

*This activity has been reviewed by the AAPA Review Panel and is compliant with AAPA CME Criteria. This activity is designated for 1 AAPA Category 1 CME credits. PAs should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation.

The recorded webinar can be accessed here.

Continuing education credits can be claimed by completing the evaluation. Both CE certificates can be found at the end of the survey.

An Allergist-Mom’s Guide to Preventing Egg Allergy

By Katie Marks-Cogan, M.D.

- A child’s risk of developing some of the most common food allergies, including egg allergy, can be reduced by up to 80% through early and sustained allergen introduction

- Egg allergy affects 2% of children and along with milk and peanut, make up 80% of childhood food allergic reactions

- The new research on food allergy prevention offers two key takeaways for parents: 1) Start introducing allergens early and 2) Keep going

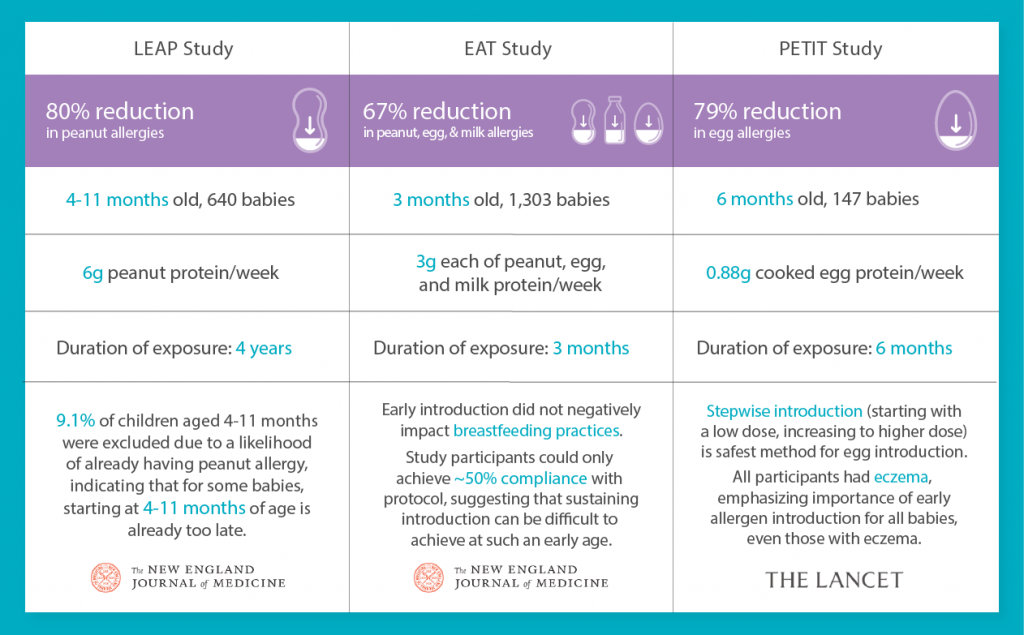

As a board-certified allergist, I see firsthand how families struggle with food allergies. Thankfully, recent landmark studies have shown that a child’s risk of developing some of the most common food allergies, including egg allergy, can be significantly reduced through early and frequent exposure to certain allergenic foods starting at 4-6 months of age. For example, the PETIT (Two-Step Egg Introduction for Allergy Prevention in Infants with Eczema) Study showed that in young infants exposed to eggs there was a 79% reduction in the overall rate of egg allergy.1

Top Allergens Affecting Children

Food allergies are on the rise and now more than 1 in 10 suffer from a food allergy in the US. Although more than 170 foods have been identified as triggers of food allergy, the FDA classifies 8 foods/food groups as major food allergens: milk, egg, peanut, tree nuts, shellfish, fish, wheat and soy.2

Egg allergy affects 2% of children and along with milk and peanut, makes up 80% of childhood food allergic reactions. Egg allergy typically presents in the child’s first year of life and ~50% of children do not “outgrow” (or become tolerant to) their egg allergy, but if they do, it may not happen until as late as their teenage years.2,3

New Research on Food Allergy Prevention

The science on food allergy prevention has changed, and the American Academy of Pediatrics, National Institute of Health, and other national organizations have all come out with new recommendations about early and sustained allergen introduction. Here’s a quick summary of the new research on food allergy prevention and how parents can now help prevent common food allergies including an egg allergy.

- LEAP Study: Reference 4

- EAT Study: Reference 5

- PETIT Study: Reference 1

However, introducing allergens can be hard to do. In fact, in the EAT study5, only half of study participants could achieve the study protocol, indicating that early and sustained introduction was difficult at such a young age. I’ve seen this both in my clinical and personal experience. When my son David was 5 months old, I realized how frustrating and time consuming early and sustained allergen introduction was, especially when most of what I offered him to eat ended up on the kitchen floor or on his bib….not in his mouth.

5 Key Lessons for Preventing Food Allergies

As an allergist and mom, there are 5 key lessons that I believe every parent needs to know about reducing the risk of food allergies in their baby:

- Start Introducing Early, Don’t Delay: Guidelines recommend starting as early as 4-6 months because there is a specific window within which our immune systems develop either a positive or negative response to certain food proteins.

- Only Introduce When It’s Best For Baby: Parents should introduce allergens for the first time only when: 1) Baby is healthy and 2) An adult can monitor for any signs of a reaction for at least 2 hours.

- Sustaining Frequent Exposure is Necessary: A baby’s immune system needs time and repeated oral exposure to develop a positive response to foods. Recent landmark studies exposed infants to allergenic foods 2-7 times/week for 3-6+ months.

- Be Persistent: Babies can be picky eaters at 4-6 months of age and it’s hard to get them to consistently eat enough. In one of the recent studies, more than 50% of parents weren’t able to stick with an early allergen introduction protocol and therefore did not necessarily see a decrease in food allergy.

- Breastfeeding + Early Introduction: While breastfeeding can be beneficial, it has not been proven that moms can prevent allergies by eating allergenic foods and exposing the baby through breast milk. It’s important for babies to get additional exposure.

While early introduction is possible to do yourself, many parents struggle to consistently feed allergenic foods as a regular part of their infant’s diet. For some helpful tips on early allergen introduction, visit this link.

For additional information on food allergen labeling visit the FDA website second on food allergens.6

Katie Marks-Cogan, M.D. is board certified in Allergy/Immunology and Internal Medicine, and treats both pediatric and adult patients. She received her M.D. with honors from the University of Maryland School of Medicine and completed her residency in Internal Medicine at Northwestern and fellowship in Allergy/Immunology at the prestigious University of Pennsylvania and Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania (CHOP). She currently works in private practice and is a member of the scientific advisory board for Ready, Set, Food!

References

- Natsume O, Kabashima S, Nakazato J, et al. Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (PETIT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Jan 21;389(10066):276-286.

- Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, et al. The Prevalence, Severity, and Distribution of Childhood Food Allergy in the United States. Pediatrics Jul2011, 128 (1) e9-e17.

- Egg Allergy. American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Version current 3 December 2019 Internet: https:// acaai.org/allergies/types-allergies/food-allergy/types-food-allergy/egg-aller- gy. Published 2014. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- DuToit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015

- Perkin MR, Logan K, Marrs T, et al. Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study: Feasibility of an early allergenic food introduction regimen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 May;137(5):1477-1486.

- What You Need to Know about Food Allergies. US Food and Drug Administration Version current 3 December 2019 Internet: https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store–serve-safe-food/what-you-need-know-about-food-allergies