U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Recommends Eggs as a First Food for Babies and Toddlers

By: Mickey Rubin, PhD, Executive Director of American Egg Board’s Egg Nutrition Center

July 15, 2020

Today is an important day for the American diet and for eggs. In an historic first, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee today issued recommendations for birth to 24 months old and specifically recommended eggs as an important first food for infants and toddlers, as well as for pregnant and lactating women.

Today’s Scientific Report also highlighted the importance of a nutrient plentiful in eggs – choline – while recommending eggs as a first food for babies to reduce risk for an egg allergy. The Advisory Committee additionally encouraged eggs for pre-teens and adolescents.

Eggs are one of the best sources of choline, an essential nutrient critical for fetal brain development. The Advisory Committee classified choline as an important nutrient that is under-consumed by all Americans. Importantly, 92% of pregnant women fail to meet the daily Adequate Intake (AI) recommendations for choline.

The Advisory Committee also specifically recommended eggs as an important first food. The latest research on food allergy prevention recommends introducing eggs when your baby is 4-6 months old and developmentally ready to help reduce the chances of developing an egg allergy. Eggs are an important first food as they provide eight essential nutrients that help build a healthy foundation for life.

Eggs are a nutritional powerhouse that contribute to health and wellbeing at every age and life stage, providing critical nutrients including protein, choline, riboflavin (vitamin B2), vitamin B12, biotin (B7), pantothenic acid (B5), iodine and selenium, which are valuable for supporting muscle and bone health, brain development and more. The Advisory Committee also noted eggs are a source of vitamin D, a nutrient of public health concern because it is under-consumed by all Americans.

Additionally, the Advisory Committee reinforced the strong body of evidence that dietary cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern. The science on eggs and cholesterol has been steadfast. The vast majority of scientific evidence shows egg consumption is not associated with cardiovascular disease. In fact, a recent Harvard University study that evaluated more than 30 years of data reaffirmed that eating eggs is not associated with cardiovascular disease. Leading health organizations such as the American Heart Association also state that eggs can be part of heart-healthy diet patterns.

As Americans are building healthier diets, you can count on eggs. For more information on building a healthy diet with eggs, please visit EggNutritionCenter.org.

Eggs and Heart Health: A Review of the Latest Research and Reports

Nutrient-rich eggs are part of heart-healthy diet patterns, according to findings from leading researchers and health authorities

By: Mickey Rubin, PhD

In 2015, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) removed dietary cholesterol from the list of nutrients of public health concern1, and this conclusion remained unchanged in the 2020 DGAC report.2 Historically, there has been a limit of 300 milligrams per day for dietary cholesterol, even though eggs were listed as a nutrient-rich food and part of healthy dietary patterns in previous guidelines.3

In making this decision, the 2015 DGA committee referenced, among other sources, a 2013 systematic review that examined the relationship between egg consumption and cardiovascular disease in almost 350,000 participants across 16 studies.4 The review and meta-analysis found no relationship between egg intake and cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, or stroke.

Since 2015, the science evaluating the relationship between dietary cholesterol, eggs, and cardiovascular health has continued to grow, with several new research studies and authoritative reports building on our existing knowledge.

LATEST RESEARCH FINDINGS FROM OBSERVATIONAL COHORTS

There are often competing headlines in nutrition science, with one study showing one thing, and another study showing the opposite. This is often true with a nutrient like cholesterol – or a food like eggs – in which our knowledge has evolved considerably over the years. Rather than getting caught with nutrition science whiplash, it is important to not focus too much on any one study, but rather view the research in totality.

For example, one observational study of U.S. cohorts published early in 2019 found a small but statistically significant increase in cardiovascular risk with egg consumption.5 However, another observational study published just a few weeks later and analyzing data from over 400,000 men and women in Europe for over an average of 12 years, found a small but statistically significant decrease in risk for ischemic heart disease with egg intake.6 While these two examples appear similar in design and provide conflicting results, additional studies published later in the year had design aspects that provided unique insights.

PURE Cohort Results Reinforce Earlier Findings and Identify New Insights

A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition assessed the association of egg consumption with blood lipids, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in three large international cohorts. [6] In one cohort, the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study, egg consumption was assessed in 146,011 individuals from 21 countries. The researchers also studied 31,544 patients with vascular disease in 2 multinational studies: ONTARGET and TRANSCEND, both of which were originally designed to test treatments for hypertension.

The findings from the PURE cohort found no link between egg consumption and cardiovascular disease outcomes. In fact, in the PURE cohort, researchers found that higher egg intake was associated with a lower risk of myocardial infarction, a finding that is consistent with other recent studies of cohorts outside the U.S.6 In the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND cohorts of individuals with vascular disease, the researchers also reported no link between egg consumption and cardiovascular events.

Thus, these findings from the PURE investigators reinforce previous research regarding egg consumption in otherwise healthy individuals, but took a big step forward in our understanding of this relationship in individuals with vascular disease.

Harvard School of Public Health Findings Reveal Decades of Strong Evidence

Yet another study was published in 2020 that was a follow-up to a landmark investigation first published in 1999. The original study, led by Hu and colleagues from the Harvard School of Public Health, reported no relationship between egg intake and coronary heart disease or stroke in women from the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) cohort and men from the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) cohort.8 At that time the researchers concluded that an egg a day did not impact heart disease or stroke risk.

The current study, an updated analysis of the study published in 1999, includes up to 24 additional years of follow-up and extends the analysis to the younger cohort of Nurses’ Health Study II.9 Thus, this latest analysis included 83,349 women from NHS; 90,214 women from NHS II; and 42,055 men from HPFS. Additionally, to compare these new findings to the extensive literature base on the topic of egg intake and cardiovascular risk, the researchers performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 27 other published studies from the U.S., Europe, and Asia.

Results from the updated analysis from NHS, NHS II, HPFS, as well as the updated meta-analysis of global cohorts are consistent:

- Egg consumption of one egg per day on average is not associated with cardiovascular disease risk overall

- Results were similar for coronary heart disease and stroke

- Egg consumption seems to be associated with a slightly lower cardiovascular disease risk among Asian cohorts

An important strength of this study is the use of repeated dietary assessments over the course of several decades in contrast to some observational cohorts which utilize only a single dietary measure at enrollment. According to the authors, it is desirable to have repeated dietary assessments over time to account for variation of dietary intake and other factors that contribute to atherosclerosis.

The studies from the PURE cohort and Harvard School of Public Health make significant contributions to the scientific literature on egg intake and cardiovascular health. These results are also consistent with the recent dietary recommendations that cholesterol is not a nutrient of public health concern.2

NEW RECOMMENDATIONS FROM LEADING HEALTH AUTHORITIES

In the past year, we have also had multiple recommendations from leading health authorities that have assessed the totality of evidence for dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular disease, as well as the role of eggs in heart healthy diet patterns across the lifespan. A common theme from these authoritative recommendations is that eggs can be a part of heart healthy diet patterns, and in some cases nutrient dense eggs should be emphasized in diet patterns due to their unique nutrient package.

In fact, the 2020 DGAC report highlights eggs and shellfish as animal-source foods, which are higher in dietary cholesterol, but not high in saturated fat as compared to other animal-source foods. This report indicates that due to the co-occurrence of dietary cholesterol and saturated fat in animal-source foods, the independent effects of these dietary components can be difficult to separate in observational studies. This observation is consistent with the most recent research and recommendations related to eggs – that is, the entire foods is more than the sum of single nutrients.2

There were no major changes to the three USDA Food Patterns recommended by the 2020 DGAC, but the value of nutrient-rich eggs was emphasized in the new dietary recommendations for infants, toddlers, and women who are pregnant and lactating. The nutrients in eggs are essential across the lifespan to support health, and for early life, to support brain development.2

American Heart Association: Eggs Fit in Heart Healthy Diet Patterns

In late 2019, the American Heart Association (AHA) Nutrition Committee published a science advisory on Dietary Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Risk.10 According to the authors, “the elimination of specific dietary cholesterol target recommendations in recent guidelines has raised questions about its role with respect to cardiovascular disease.” This review examined evidence from observational cohorts and randomized controlled trials and concluded that “a recommendation that gives a specific dietary cholesterol target within the context of food-based advice is challenging for clinicians and consumers to implement; hence, guidance focused on dietary patterns is more likely to improve diet quality and to promote cardiovascular health.” The science advisory recommends heart-healthy eating patterns such as the Mediterranean-style and DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension)–style diets. Specifically, regarding eggs, the advisory concluded:

- Healthy individuals can include up to a whole egg daily in heart-healthy dietary patterns.

- For older healthy individuals, given the nutritional benefits and convenience of eggs, consumption of up to 2 eggs per day is acceptable within the context of a heart-healthy dietary pattern.

- Vegetarians who do not consume meat-based cholesterol-containing foods may include more eggs in their diets within the context of moderation.

Australian Heart Foundation: No Evidence to Limit Egg Consumption

It wasn’t only the American Heart Association that clarified the role of eggs in a heart healthy diet, but the Australian Heart Foundation (AHF) made similar recommendations with a new position statement on eggs and cardiovascular health.11 The AHF summary of evidence concluded there is no evidence to suggest any limit on egg consumption for normal, healthy individuals. The review does suggest a limit to fewer than 7 eggs per week for those with type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease that require LDL cholesterol- lowering interventions.

Both the AHA and AHF guidelines were clearly a step forward, building on the knowledge that dietary cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern in healthy individuals.

SUMMARY

The science on dietary cholesterol and eggs continues to grow and demonstrates that eggs are an important part of healthy dietary patterns across the lifespan. Overall, these data support the value of eggs as a nutrient dense food within healthy dietary patterns. As a good or excellent source of eight essential nutrients including choline, six grams of high quality protein, 252 mcg of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin, the 70 calories of an egg can be viewed as so much more than just a source of dietary cholesterol.

See our recipes that fit into a heart-healthy diet or heart health toolkit for more information.

References

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture,. 2015

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services,. 2020; Available from: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/ScientificReport_of_the_2020DietaryGuidelinesAdvisoryCommittee_first-print.pdf

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture,. 2010

- Shin, J.Y., et al., Egg consumption in relation to risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr, 2013. 98(1): p. 146-59.

- Zhong, V.W., et al., Associations of Dietary Cholesterol or Egg Consumption with Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. JAMA, 2019. 321(11): p. 1081-1095.

- Key, T.J., et al., Consumption of Meat, Fish, Dairy Products, Eggs and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease: A Prospective Study of 7198 Incident Cases Among 409,885 Participants in the Pan-European EPIC Cohort. Circulation, 2019. 18;139(25):2835-2845.

- Dehghan M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, et al. Association of egg intake with blood lipids, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 177,000 people in 50 countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111(4):795-803.

- Drouin-Chartier JP, Chen S, Li Y, et al. Egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: three large prospective US cohort studies, systematic review, and updated meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;368:m513. Published online 2020 Mar 4.

- Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, et al. A prospective study of egg consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women. JAMA. 1999;281(15):1387-1394.

- Carson JAS, Lichtenstein AH, Anderson CAM, Appel LJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Meyer KA, Petersen K, Polonsky T, Van Horn L; on behalf of the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Stroke Council. Dietary cholesterol and cardiovascular risk: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140: e-pub ahead of print.

- Australian Heart Foundation; Eggs and Cardiovascular Health: Summary of Evidence. 2019.

Every Bite Counts: Why Eggs are an Important First Food

By: Jen Houchins, PhD, RD

The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee says “every bite counts” when it comes to feeding infants and toddlers. This is the first time in Dietary Guidelines history that the DGAC is making recommendations for the Birth to 24-month lifestage and addresses complementary feeding as “a critical period for growth and development… characterized by high nutrient needs in relation to the amount of food consumed.1”

The Advisory Committee specifically recommended eggs as an important first food for infants and toddlers as they are a rich source of choline and because early introduction of eggs (after 4 months of age), when baby is developmentally ready, may help reduce the risk of developing a food allergy.

The following breaks down recommendations from the Advisory Committee based on age group.

BIRTH TO 6 MONTHS

For approximately the first 6 months of age, human milk, infant formula, or a combination of the two are an infant’s sole source of nutrition. Once developmentally ready (>4 months of age) – baby has good head and neck control, can sit upright, has lost the tongue-thrust reflex, and shows interest in food – complementary foods can be introduced.

6-12 MONTHS

During the 6-12 month period, an infant continues to receive human milk, infant formula, or a combination of the two, but also starts transitioning to a varied diet that includes complementary foods and beverages. This is where nutrient-rich foods with essential nutrients for growth and development come into play. The Advisory Committee recommends a variety of animal-source foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy), fruits, and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and whole grain products in age-appropriate forms, beginning at ages 6 to 12 months, to provide key nutrients and build healthy dietary habits.

For infants fed human milk, the Committee recommends complementary foods that contain iron and zinc, such as meats and fortified infant cereals. Modest amounts, (i.e., less than 1 ounce equivalent per week), of seafood, eggs, and nuts is recommended for infants 6 to 9 months and minimum weekly amounts of 3 oz seafood, 1 egg, and 0.5 oz, respectively, by ages 9 to 12 months. Further, the DGAC recommends prioritizing fruits and vegetables, particularly those rich in potassium, vitamin A, and vitamin C, to provide adequate nutrition, but also to foster acceptance of these healthy foods.

During this time, the Committee also recommends the introduction of peanut-containing foods and eggs, to help reduce the risk of developing food allergies. Additionally, introducing baby to complementary foods like eggs, which are high in choline, supports brain health.2,3 It should also be noted that complementary feeding not only provides additional nutrients, but introduces different textures, and models healthy eating behaviors, as well. The table below outlines approximate amounts of complementary foods and beverages for ages 6 to 12 months.1

12-24 MONTHS

As baby moves past the 12-month mark and into the second year of life, many move away from human milk and infant formula entirely and transition to a fully varied diet of nutrient-rich foods and beverages. Others may choose to continue offering human milk in addition to a varied diet of nutrient-rich foods and beverages. Either way, the food patterns for this age group is consistent with proportions of food groups and subgroups recommended for children ages 2 years and older, which requires careful choices of foods to meet nutrient needs. The DGAC emphasizes offering developmentally appropriate forms of nutrient-rich animal-source foods, including meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy products, as well as nut and seed containing foods, fruits, vegetables, and grain products in age-appropriate forms. For toddlers whose diets do not include meat, poultry, or seafood, the Committee recommends eggs and dairy products on a regular basis, along with soy products and nuts or seeds, fruits, vegetables, grains, and oils. The tables below outline approximate amounts of foods and beverages for toddlers between the ages of 12 to 24 months, for those not receiving human milk or infant formula, those fed human milk, and for those following a vegetarian style eating pattern.1

EGGS AS A FIRST FOOD FOR INFANTS AND TODDLERS

Eggs are recommended after four months and when baby is developmentally ready for complementary foods, and throughout infancy and toddlerhood.

- Eggs are a nutrient-rich choice providing a good or excellent source of eight essential nutrients.

- Eggs provide various amounts of all the nutrients listed by the American Academy of Pediatrics4 as essential for brain growth.

- Introducing eggs early and often may help reduce risk of developing an allergy.

- Eggs are an affordable source of high-quality protein.

- Eggs are versatile and can be used to make a wide variety of dishes and can be adjusted to fit various developmental stages and age-appropriate textures.

Interested in more information?

- Handout: Eggs as a First Food Infographic

- Handout: Pregnancy and Birth to 24 Months toolkit

- Read: Eggs – An Essential Complimentary Food

- Read: Early Introduction of Eggs May Reduce the Risk of Developing an Egg Allergy

Check out these recipes for infants and toddlers:

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Sweet Potato Soufflé

- Recipe: Eggy Peanut Butter Muffins

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Oatmeal with Egg

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Egg Scramble

- Recipe: Savory Egg Veggie Pancake

- Recipe: Baby’s First Pancakes

- Recipe: Egg Veggie Casserole

References

- Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services,. 2020; Available from: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-07/ScientificReport_of_the_2020DietaryGuidelinesAdvisoryCommittee_first-print.pdf

- Wallace, T.C., A Comprehensive Review of Eggs, Choline, and Lutein on Cognition Across the Life-span. J Am Coll Nutr, 2018. 37(4): p. 269-285.

- Wallace, T.C., et al., Choline: The Underconsumed and Underappreciated Essential Nutrient. Nutr Today, 2018. 53(6): p. 240-253.

- Schwarzenberg, S.J., et al., Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health. Pediatrics, 2018. 141(2)

Early introduction of eggs may reduce the risk of developing an egg allergy

By: Jen Houchins, PhD

Previous recommendations for infant feeding included guidance to avoid early introduction of eggs and allergenic foods in the diet for both the infant1 and mother.2 However, science has advanced, and early life feeding recommendations are rapidly changing. The 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) evaluated evidence for complementary feeding, and allergy experts chimed in with the latest scientific evidence.3 The Advisory Committee affirmed that current research indicates that introducing peanut and egg, in an age-appropriate form, in the first year of life (>4 months) may reduce the risk of allergy to peanut and eggs. For other type of potentially allergenic foods, the DGAC reported there is no evidence that avoiding such foods in the first year of life is beneficial.

LATEST RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EARLY INTRODUCTION

The Advisory Committee recommends that caregivers provide a variety of animal-source foods (meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, and dairy), fruits, and vegetables, nuts and seeds, and whole grain products, beginning at ages 6 to 12 months in order to provide essential nutrients, develop acceptance of nutrient-rich foods, and help build lifelong dietary habits. Additionally, early introduction of peanuts and eggs has the potential to favorably influence risk of allergy to these foods.

According to a recent systematic review conducted for the USDA and the Department of Health and Human Services Pregnancy and Birth to 24 months project, “…there is evidence to suggest that introducing allergenic foods in the first year of life (>4 months) does not increase risk of food allergy or atopic dermatitis but may prevent peanut and egg allergy…Moderate evidence suggests that introducing egg in the first year of life (>4 months) may reduce the risk of food allergy to egg.”4 This conclusion aligns with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Clinical Report on early nutritional interventions, which states, “There is no evidence that delaying the introduction of allergenic foods, including peanuts, eggs, and fish, beyond 4 to 6 months prevents atopic disease.”5 A recent analysis of the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) randomized controlled trial found “early introduction was effective in preventing the development of food allergy in specific groups of infants at high risk of developing food allergy…Of equal importance was that early introduction of allergenic foods into the diets of the non-high-risk infants was not associated with any increased risk of food allergy.”6 High risk infants in this study were identified as those with visible eczema at enrollment and infants with food sensitization (IgE antibodies present to one or more of the six allergenic foods). In this secondary analysis, early introduction of egg reduced the risk of allergy for both infants sensitized to egg and for those who had moderate to severe eczema at enrollment. Food Allegy Research and Education (FARE) has also commented on this new study, and suggests, “Guidance on early egg introduction is likely to evolve as more evidence becomes available.”

BAKED EGGS ARE TOLERATED BY MANY CHILDREN WITH EGG ALLERGY

In the U.S., approximately 1% of all children, and about 12% of children with food allergies are allergic to eggs.7 Egg allergies are considered to have a high rate of resolution in childhood, with approximately 50% of children with egg allergy reaching tolerance between the ages of 2-9 years.8,9

Of significant interest, it has been observed that approximately 70% of children with egg allergy can tolerate extensively baked egg in foods like muffins or cakes (as opposed to lightly cooked eggs like scrambled or French toast).9-11 Several studies have suggested that introduction of baked egg in the diet of children who can tolerate these foods may help hasten resolution of allergy,9-11 with some data showing frequent ingestion increases the likelihood of tolerance compared to infrequent ingestion.12

Although these are promising observations, many of these recent studies lack adequate control groups, limiting conclusions of the impact of extensively baked egg on allergy progression or development of tolerance.11 So, while more research is needed to better understand the role of baked eggs to potentially alter the course of egg allergy, “…inclusion of egg and milk in its baked form may also have other benefits. It is reasonable to expect that liberation of the diet may boost nutrition, improve the child and family’s quality of life and reduce family anxiety, however, no studies have specifically investigated this.”11 Importantly, caregivers of children with egg allergy should consult the child’s physician before introducing extensively baked egg into the child’s diet.

ADDITIONAL BENEFITS OF EARLY INTRODUCTION

Early introduction of eggs into an infant’s diet has the added benefit that eggs provide various amounts of all nutrients listed by the American Academy of Pediatrics as essential for brain growth.13 Eggs additionally provide 252 mcg of lutein + zeaxanthin, carotenoids with emerging evidence linking to brain development and health.14,15 As a nutrient-rich food that is a good or excellent source of eight essential nutrients, including choline – a nutrient essential for brain development and health, incorporation of eggs into the diet early may not only reduce the risk of food allergy to egg, but also serve as an important food to support brain development.

Interested in more information?

- Handout: Eggs as a First Food Infographic

- Handout: Pregnancy and Birth to 24 Months toolkit

- Watch: LEAPing Past Food Allergies webinar

- Read: An Allergist Moms Guide to Preventing Egg Allergy

- Watch:Jessica Ivey on WBRC Fox 6 News

- Read: Eggs – An Essential Complementary Food

Check out these recipes for infants and toddlers:

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Sweet Potato Soufflé

- Recipe: Eggy Peanut Butter Muffins

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Oatmeal with Egg

- Recipe: Peanut Butter Egg Scramble

- Recipe: Savory Egg Veggie Pancake

- Recipe: Baby’s First Pancakes

- Recipe: Egg Veggie Casserole

References:

- Zeiger, R.S., Food allergen avoidance in the prevention of food allergy in infants and children. Pediatrics, 2003. 111(6 Pt 3): p. 1662-71.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics, 2000. 106(2 Pt 1): p. 346-9.

- Spergel, J.M., et al. Public comments to the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2020 1-July-2020]; Available from: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FNS-2019-0001-17765.

- Obbagy, J.E., et al., Complementary feeding and food allergy, atopic dermatitis/eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr, 2019. 109(Supplement_7): p. 890s-934s.

- Greer, F.R., S.H. Sicherer, and A.W. Burks, The Effects of Early Nutritional Interventions on the Development of Atopic Disease in Infants and Children: The Role of Maternal Dietary Restriction, Breastfeeding, Hydrolyzed Formulas, and Timing of Introduction of Allergenic Complementary Foods. Pediatrics, 2019. 143(4).

- Perkin, M.R., et al., Efficacy of the Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study among infants at high risk of developing food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2019. 144(6): p. 1606-1614.e2.

- Gupta, R.S., et al., The Public Health Impact of Parent-Reported Childhood Food Allergies in the United States. Pediatrics, 2018.

- Sicherer, S.H. and H.A. Sampson, Food allergy: A review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018. 141(1): p. 41-58.

- Savage, J., S. Sicherer, and R. Wood, The Natural History of Food Allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract, 2016. 4(2): p. 196-203; quiz 204.

- Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. and A. Fiocchi, Rare, medium, or well done? The effect of heating and food matrix on food protein allergenicity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol, 2009. 9(3): p. 234-7.

- Dang, T.D., R.L. Peters, and K.J. Allen, Debates in allergy medicine: baked egg and milk do not accelerate tolerance to egg and milk. World Allergy Organ J, 2016. 9: p. 2.

- Peters, R.L., et al., The natural history and clinical predictors of egg allergy in the first 2 years of life: a prospective, population-based cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2014. 133(2): p. 485-91.

- Schwarzenberg, S.J. and M.K. Georgieff, Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health. Pediatrics, 2018. 141(2).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and Agricultural Research Service. FoodData Central. 2019; Available from: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/index.html.

- Johnson, E.J., Role of lutein and zeaxanthin in visual and cognitive function throughout the lifespan. Nutr Rev, 2014. 72(9): p. 605-12.

Choline Throughout the Life-Span

By: Katie Hayes, RDN

WHY IS CHOLINE IMPORTANT?

Choline is an essential nutrient, meaning that we must consume adequate amounts in the diet to achieve optimal health. Unfortunately, most people do not consume enough choline. In fact, more than 90% of Americans (including approximately 90% of pregnant women) fail to meet the adequate intake.1 The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee has classified choline as a nutrient that poses special challenges for Americans due to underconsumption and encouraged eggs for pregnant women, as a complementary food for babies and toddlers, and for pre-teens and adolescents.2 Many foods offer choline in small amounts, however, only a few foods are significant choline sources. Furthermore, most multivitamin supplements contain little, if any, choline. Fortunately, eggs are convenient, affordable, accessible, and an excellent source of choline.

Beginning in fetal development, Choline is critical to good health and remains essential throughout the lifespan. This nutrient is important in many ways.

- During pregnancy, choline helps the baby’s brain and spinal cord develop properly and supports brain health throughout life.

- Infants and young children need choline for continued brain development and health.

- Choline is part of a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which is important for muscle control, memory and mood.3

- Choline is also important for the support of membranes that surround your cells, the transportation of fats throughout the body and for liver health.

- New research is exploring how choline throughout life may have lasting effects on cognition and prevention of cognitive decline.4

HOW MUCH CHOLINE DO WE NEED?

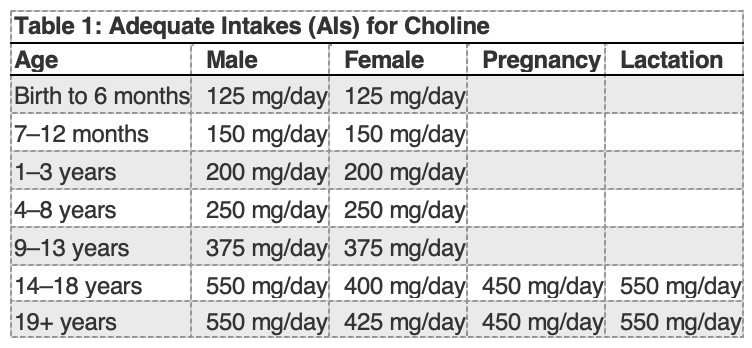

The amount of choline an individual needs depends on many things, including age, gender and stage of life. Table 1 lists the current Adequate Intakes (AIs) for choline.3

WHAT FOODS HAVE CHOLINE?

People of all ages need adequate choline for good health, but very few consume enough through food and supplements. While many foods contain some choline, only a handful of foods are considered good or excellent sources. Fortunately, two large eggs (about 300mg of choline) contain more than half of the recommended intake for pregnant women and can help them meet their needs. The table below lists food sources of choline.2

CHOLINE & COGNITION

Choline plays a role in early brain development during pregnancy and infancy. There is evidence that infants exposed to higher levels of maternal choline (930 mg/day) during the third trimester have improved information processing speed, an indicator of cognitive function,4,5 during the first year of life.

The American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates recommended the addition of choline to prenatal vitamins because of its essentiality in promoting cognitive development of the offspring.6 This recommendation from AMA highlights the increased recognition of choline as a nutrient of concern. The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) also list choline as a nutrient under consumed by most Americans. The DGAs recommend individuals shift to healthier eating patterns to help meet nutrient needs, including choline.7

Interested in more information about choline?

- Read: Choline – The Underconsumed and Underappreciated Essential Nutrient

- Handout: Important Nutrients for Brain Health

- Watch: Brain Health

- Read: Research News – Choline, Lutein, and Cognition

- Watch: Jessica Ivey on WBRC Fox 6 News

- Recipe: Sweet and Savory Breakfast Bowl by Mary Ellen Phipps, RD

- Watch: Mind Your Eggs + Veggies: Nutrition for Cognitive Health webinar

References:

- Wallace TC, Fulgoni VL III. Assessment of total choline intakes in the United States. J Am Coll Nutr 2016, 35(2), 108-112.

- National Institutes of Health. Fact Sheet for Health Professionals: Choline. Version current 26 September 2018. ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Choline-HealthProfessional/Accessed June 22, 2020.

- Wallace TC. A comprehensive review of eggs, choline, and lutein on cognition across the life-span. J Am Coll Nutr 2018, 37(4), 269-285.

- Caudill MA, et al. Maternal choline supplementation during the third trimester of pregnancy improves infant information processing speed: a randomized, double-blind, controlled feeding study. FASEB J. 2018;32:2172-2180.

- AMA Wire. AMA backs global health experts in calling infertility a disease. https://wire.ama-assn.org/ama-news/ama-backs-global-health-experts-calling-infertility-disease

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. Available at http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.